Logical Reasoning and Knowledge Discovery →

When a Deep Learning algorithm invented Halicin, there was instant speculation about the ability of Deep Learning algorithms to discover new knowledge which in this case was a new antibiotic compound. This compound also seemed to have a new structure that was different from existing antibiotic compounds. Does this constitute new knowledge? Of course, it does. After all, the structure of the compound was not known earlier. This is akin to solving a Sudoku puzzle by searching through an enormous search space and arriving at a solution. The solution is new knowledge - depending on the way you look at it.

While AI systems today are more akin to analogy machines than reasoning machines there is an intense debate about what kind of a machine would lead us to our quest of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) - is the ability to reason needed at all? After all, human beings ourselves learn more through experiences and we reason more from our past experiences than from the rule book. However, according to Stanislas Dehaene’s book How We Learn we have certain intuition built into our brain that enables us to learn abstract concepts. In his book, he notes:

Characteristic of the human species is a relentless search for abstract rules, high-level conclusions that are extracted from a specific situation and subsequently tested on new observations … Learning means managing an internal hierarchy of rules and trying to infer the most general ones that summarize a whole series of observations.

This looks similar to logical reasoning (in the sense of mathematical logic in the realm of formal methods) where conclusions are inferred from hypotheses using a sequence of deduction rules. In order to illustrate this, let me pick one of the puzzles from TPTP library - the Aunt Agatha puzzle which is as follows:

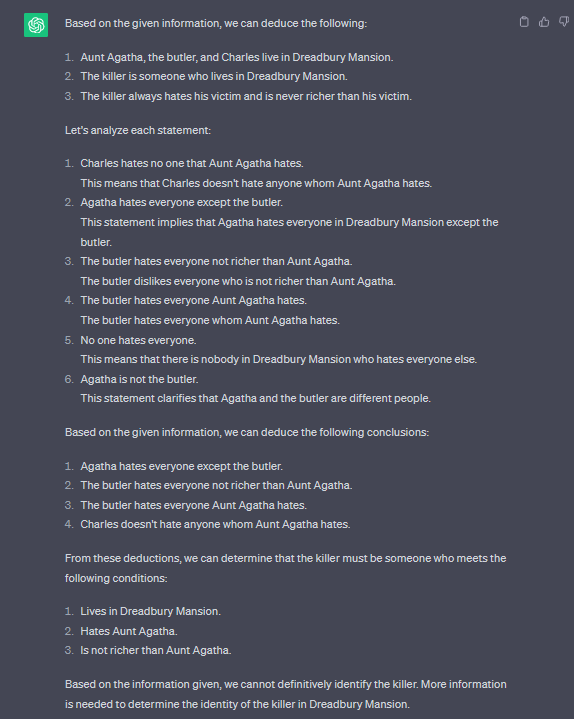

Someone who lives in Dreadbury Mansion killed Aunt Agatha. Agatha, the butler, and Charles live in Dreadbury Mansion, and are the only people who live therein. A killer always hates his victim, and is never richer than his victim. Charles hates no one that Aunt Agatha hates. Agatha hates everyone except the butler. The butler hates everyone not richer than Aunt Agatha. The butler hates everyone Aunt Agatha hates. No one hates everyone. Agatha is not the butler. Therefore: Agatha killed herself.

If one were to encode the given facts in mathematical logic and prove the conclusion (the conjecture that Agatha killed herself) is deducible from the given facts, say in a theorem prover (like Vampire), it would be able to not only prove the conjecture, the logical reasoning system in Vampire would be able to show the sequence of steps that was used to arrive at the conclusion from the assumptions.

29. lives(sK0) [cnf transformation 26]

30. killed(sK0,agatha) [cnf transformation 26]

...

...

...

79. ~hates(butler,butler) [superposition 41,78]

...

...

82. hates(charles,agatha) <- (1) [backward demodulation 44,57]

89. ~hates(agatha,agatha) <- (1) [resolution 82,37]

...

...

93. $false [avatar sat refutation 66,71,81,92]

A Vampire proof run would also discover new knowledge (i.e. new facts not explicitly stated in our input set of facts). For example, it could deduce that the butler does not hate himself (line 79 above) which is not explicitly mentioned in the set of assumptions (derived from our natural natural language text). Such a kind of logical reasoning would be a great cornerstone for explainable AI systems of the future. However, languages themselves are ambiguous and translating from an ambiguous natural language into an unambiguous formulas in first order logic (as in this case) is not a trivial task. Maybe, just maybe one could generate such formulas themselves by training a model using a large corpus of natual language text and the corresponding logical formulas that would be able to capture the essence of natual language statements, context, etc. in logical form.

It was however not able to deduce new knowledge or to conclude if Agatha killed herself.

Note that the present day AI systems though demonstrate exemplary generative skills across text, images and video, the content generated, though novel in some cases, is an emergent behavior that arises from the vast knowledge base the model was trained on. Hence, it still lacks the capability to reason how it generated a particular content (it can not produce a sequence of deductions for example).

A symbiotic combination of logical reasoning and analogy based reasoning would enable both an efficient generation of impressive content while at the same time being able to reason about the chain of thought involved in the process. GreaseLM and LEGO are research efforts towards infusing reasoning capabilities in language models. They however work on pruning and traversing a knowledge graph based on the context from embedding vectors, rather than translating the knowledge into formulas in mathematical logic. AI systems that need to solve problems in mathematics and to derive new knowledge in the form of new mathematical proofs or conjectures would need more rigour and encoding the knowledge of mathematics in the form of logical formulas and training AI systems on such a corpus could be one way of achieving reasoning capabilities. Besides solving competitive math problems, such systems might be able to discover new physical structures that are lighter and stronger, or better algorithms that are currently unknown, better deterministic optimal algorithms in the place of present day heuristics, or even proofs of non-existence of better algorithms for certain problems.

The annotated logical encoding of the Aunt Agatha problem in TPTP syntax is provided below:

% axioms

% a1: someone who lives in D Mansion (DM) killed Agatha

fof(a1, axiom,

? [X] : (lives(X) & killed(X, agatha))).

% a2_0, a2_1, a2_2: Agatha, Butler and Charles live in DM

fof(a2_0, axiom,

lives(agatha)).

fof(a2_1, axiom,

lives(butler)).

fof(a2_2, axiom,

lives(charles)).

% a3: Agatha, Butler and Charles are the only people who live in DM

fof(a3, axiom,

! [X] : (lives(X)

=> ( X = agatha

| X = butler

| X = charles))).

% a4: A killer always hates his victim

fof(a4, axiom,

! [X, Y] : ( killed(X, Y)

=> hates(X, Y))).

% a5: A killer is never richer than his victim

fof(a5, axiom,

! [X, Y] : ( killed(X, Y)

=> ~richer(X, Y))).

% a6: Charles hates no one that Aunt Agatha hates

fof(a6, axiom,

! [X] : ( hates(agatha, X)

=> ~hates(charles, X))).

% a7: Agatha hates everyone except the Butler

fof(a7, axiom,

! [X] : ( (X != butler)

=> hates(agatha, X))).

% a8: The Butler hates everyone not richer than Aunt Agatha

fof(a8, axiom,

! [X] : ( ~richer(X, agatha)

=> hates(butler, X))).

% a9: The Butler hates everyone Aunt Agatha hates

fof(a9, axiom,

! [X] : ( hates(agatha, X)

=> hates(butler, X))).

% a10: No one hates everyone

fof(a10, axiom,

! [X] : ? [Y] : ~hates(X, Y)).

% a11: Agatha is not the Butler

fof(a11, axiom,

(agatha != butler)).

% c1: Agatha killed herself

fof(c1, conjecture,

killed(agatha, agatha)).